Romana Echensperger MW, eine gute Freundin von mir hat vor einiger Zeit für GuildSomm einen wunderbaren Artikel über deutschen Spätburgunder geschrieben.

Damit möchte ich meine Serie über Pinot Noir starten. Es werden viele Berichte zu meiner Lieblings-Rebsorte folgen.

Die Serie wird von Winzern, Weinlagen, Ländern, Weinmaking und dem Zauber der schönsten Pinots handeln.

Pinot Noir with an Umlaut: German Spätburgunder

German Pinot Noir is a grotesque and ghastly wine that tastes akin to a defective, sweet, faded, diluted red Burgundy from an incompetent producer.

-Robert Parker, 2002.

Do you still have this picture in your mind when it comes to German Pinot Noir? Then it is time for an update, because even in 2002 our dear friend Mr. Robert Parker was out of date concerning German Pinot Noir.

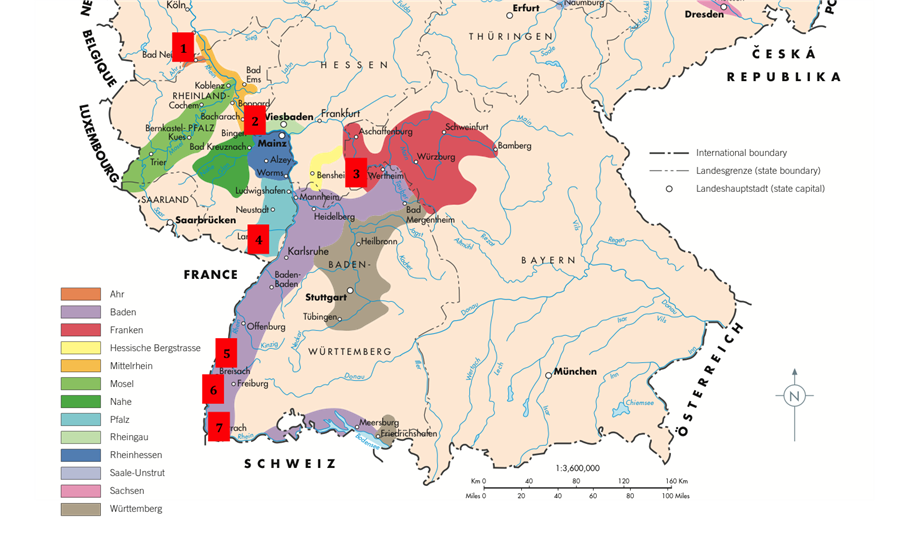

The Spread of Spätburgunder

First of all, the acreage of Spätburgunder in Germany is rising. After France and the United States, Germany is the third largest producer of Pinot Noir in the world – ahead of New Zealand and Switzerland. Plantations of Pinot Noir in Germany have doubled since 1990 to 11,758 hectares today, and Spätburgunder is the third most-planted grape variety in Germany, after Riesling and Müller-Thurgau.

| France | 26,337 ha |

| USA | 15,802 ha |

| Germany | 11,756 ha |

| New Zealand | 4,650 ha |

| Switzerland | 4,449 ha |

| Australia | 4,254 ha |

| Italy | 3,300 ha |

| Argentina | 1,441 ha |

| Chile | 1,382 ha |

| Austria | 409 ha |

| 1964 | 1,839 ha |

| 1979 | 3,573 ha |

| 1991 | 6,449 ha |

| 2000 | 9,255 ha |

| 2009 | 11,733 ha |

| 2011 | 11,756 ha |

A little bit of history

Spätburgunder has a long tradition in German vineyards, especially in Baden where it was first documented in the year 884 at Lake Constance. The emperor Charles III, better known as “Charles the fat,” a great-grandchild of Charlemagne, brought the variety from Burgundy, where it is most probably native, to the south of Germany. In comparison, Riesling was first documented in Germany much later, in the year 1435. Furthermore, Pinot Noir was starting to become widely spread from the 15th century onwards, thanks to Cistercian monasteries like Kloster Eberbach.

German Clones – the key to a unique taste

Since Pinot Noir is a grape variety that is prone to mutation, it is not surprising that during the long history of growing in Germany a unique clonal selection of Pinot Noir took place. In the 1930s, the first clonal selections were made in Assmannshausen in the Rheingau. In those times, Pinot Noir was deemed to be a degenerated grape variety. The plants were infected with viruses and therefore yielding unreliably. The second wave of clonal selection came after the Second World War in the 1950s, with targets that mirrored the preoccupations of the age: must weight and yield were the most important parameters, resulting in high-yielding vines with high must weights, yet compact, so-called “standard” clones.

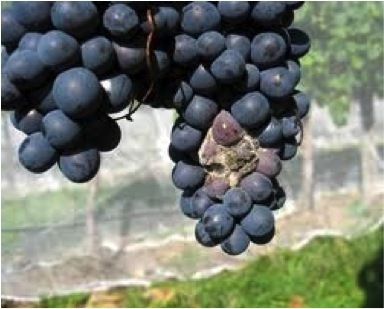

The “standard” clones are in several ways a negative thing. Pinot Noir is one of the grape varieties where yield really matters. While one can easily make great Cabernet Sauvignon with a yield of 50-60 hl/hectare, Pinot Noir is good only when less then 40 hl/hectare are harvested, and really great wines are made with about 30 hl/hectare. Furthermore, Pinot Noir is a thin-skinned grape variety. Since color and flavor are located in the skin, the big berries of the “standard” clones have a bad skin-to-pulp/juice ratio, and it is nearly impossible to make a structured wine out of those bunches. Furthermore, the compacted berries are more susceptible to botrytis. While noble rot is welcomed with Riesling, in red wine it is a disaster because the fungus develops an enzyme called laccase, which destroys all color. The only way to overcome the problem is to heat up the must (if one doesn’t want to have orange-colored wine after a few months). Nowadays, most of the growers who still have those clones in their vineyards divide the bunches after flowering. As a result, clusters grow longer and the berries are therefore less compacted. However, from the 1950s until the 1970s growers preferred high yields, and thermo-vinification was widely used. I assume Robert Parker tasted one of those German “reds” when he described German Pinot Noir as “grotesque and ghastly.“

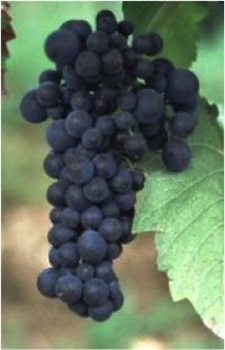

Rot-susceptibility of those “standard” clones and the efforts of a new generation of wine growers to increase quality have led to research and selection of new clones. Today a plethora of German clones are registered, and the new generation of small and mixed-berried clones with loose bunches, like the Geisenheim “20-13 Gm” or the Freiburg “FR 1801,” are in favor. Equally popular is the planting of the famous French “Dijon” clones. Wine made from German Spätburgunder clones shows more upfront red fruit, with a hint of lovage, and some of these clones are known for keeping high acidity levels. Wine made from French clones, on the other hand, has a darker fruit expression in general and very often has an earthy aromatic core. It is important to know the history of Pinot Noir in Germany to understand why Spätburgunder very often tastes so typically German.

However, there is not ONE right clone and most of the growers prefer to plant a mix of clones. Furthermore, it became clear that the famous “Dijon” clones are not suited to warmer climates, such as the sub-region Kaiserstuhl in Baden. The “Dijon” clones were selected for many traits, most significantly their ability to ripen relatively early in the Côte d’Or. In some warmer sites this means a tendency towards a very rapid sugar accumulation. Here some German clones, such as the „Mariafeld“ clones from Freiburg (like the FR 13L), are known to retain high acidity and have an advantage.

The so-called “standard” clone (left picture), developed in the 1950s, with the selection target of high must-weight and high yield. Big, compact bunches and therefore increased risk of botrytis infection was the result. On the right is an example of the latest clonal development in Germany: clone “Gm 20-13” from the research centre in Geisenheim, Rheingau. The selection target was more intense varietal character, more color, higher extract, lower yield as well as smaller and mixed berries within one cluster, so as to be less susceptible to rot.

Climate Change

Research at the famous Humboldt University in Berlin shows that average air temperature in Germany has increased with 1.4°C over the last 40 years. Red winemaking in this marginal climate is a new ball game.

Winemaking Techniques

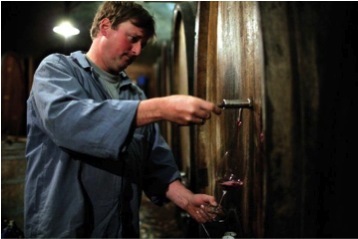

Pioneers like Bernhard Huber from Baden or the Knipser brothers from the Pfalz region learned the secrets of Spätburgunder winemaking by trial and error, as well as through trips to Burgundy and discussions with the French Pinot Noir masters. The new generation of growers has self-evidently studied oenology and most of them have had the opportunity to do an internship abroad. Nowadays you rarely see thermo-vinification anymore (except perhaps in big-scale cooperatives). Most of the producers are mastering the art of Spätburgunder production from the vineyard to the cellar.

Widespread nowadays is the practice of pre-fermentation cold-maceration, aiding colour/aroma extraction for premium wines. Whole-bunch-fermentation was first adopted by pioneers like Rudolf Fürst (winery Paul Fürst / Franken) and is now practiced on a broader scale. This indicates better ripening due to climate change and better clonal selection, encouragement of intra-cellular fermentation for increased aromatics as well as tannin extraction for longevity and structure. On a very low scale must concentration (i.e. reverse osmosis) is used, although it was more prominent 15 years ago (experience shows that this was not supportive to the overall quality). However, since Pinot Noir is known to be anything but a “sugar factory” in the vineyard, chaptalisation is still widely used. Even high-class growers like Bernhard Huber admit, that they sometimes need an extra of a ½% alcohol to enforce balance and mouthfeel.

Whether it is the use of stems during fermentation, cold-maceration à la Henri Jayer, or the decision about which and how much new oak to use, today’s highly educated and experienced growers make reasoned decisions regarding the appropriate pathways to take through all the possible winemaking opportunities regarding Pinot Noir. Today they can better express their ideas of what high-quality Spätburgunder should be about.

Different Terroirs

While the famous Pinot Noirs of Burgundy stem from limestone soils of the Jurassic age, like the fossil-rich Bajocian found in the northern Côte de Nuits or the Argovian limestone more prone to erosion in the Côte de Beaune, Spätburgunder in Germany is planted on very different soils. Since the 1980s growers returned to the concept of terroir and away from the German quality classification wherein only sugar level counts.

Since Riesling mirrors terroir perfectly, Pinot Noir is the perfect completion as THE terroir-driven red grape for cool climates.

Below are a few examples of very good Pinot Noir terroirs in Germany:

1: The Ahr Valley

With 548 hectares, the Ahr Valley is one of the smallest wine regions in Germany. Although it is one of the northernmost areas, 90% is planted with red varieties. With 60% of the vineyard area, Spätburgunder is the most important one. The preference for red varieties is due to the very sheltered microclimate and the soil type: the Ahr valley is a slate and graywacke canyon, protected from too much precipitation and wind by the Eifel ridge. Most of the terroirs in that region are based on slate and graywacke, which heat up easily and store heat. Only a few exceptions exist in the lower Ahr valley, between the villages Bad Neuenahr and Heimersheim, where deeper soils like loamy loess can be found. This terroir, combined with predominantly German clones, are responsible for a very distinctive character: upfront ripe, very cassis-like fruit mingled with smoky and flinty tones. Furthermore, the wines are very juicy, with smooth tannins but nevertheless holding ageing potential. The issue here is the strong domestic market due to the proximity of the wealthy metropolitan area around Cologne, and prices are therefore sometimes ridiculously high.

Best Producers: Jean Stodden, Meyer-Näkel, Adeneuer, and Deutzerhof

Single vineyard Pfarrwingert in the village Dernau (left picture) shows the typicity of the Ahr region: steep slopes with poor soils made of slate and greywacke. Meike Näkel of the winery Meyer-Näkel (right picture) makes textbook Ahr Spätburgunder known for an upfront, almost Cassis-like fruit expression.

2: Assmannshausen in the Rheingau

The village of Assmannshausen lies at the point where the river Rhine returns to its normal direction of flow from south to north. Pinot Noir has been cultivated in this area for more than 500 years. The south- and southwest-facing slope is made of predominantly slate, with loamy loess on the lower slope. Some of the growers are taking care of tradition, maturing their Pinot Noir wines in big old barrels and producing an overall lighter and filigreed red wine, while others like the famous August Kessler follow a more international stylebook by reducing their yields and using barriques for their best wines. Kesseler’s wines show immense ageing potential and very dense black fruit, underlined with freshness and spicy slate tones as well as a silky, elegant texture and long finish. He is in my opinion the best red wine producer in Assmannshausen.

3: Bürgstadt and Klingenberg in Franken

Around the village of Bürgstadt, one can find the single vineyards Centgrafenberg and Hundsrück, and around Klingenberg are the very steep slopes of the single vineyard Schlossberg. They all face south, and are composed of Trias sandstone with different levels of loam. The most shallow soils in each are planted with Pinot Noir. Of course, other wineries are located here too, but the most important one (available in various export markets) is Fürst. Paul Fürst has planted a mix of German and French clones in his vineyards and since he is one of THE Spätburgunder pioneers in Germany, he truly masters the art of winemaking. He was one of the first who used stems during fermentation. The wines are very often quite tight in their youth, but they develop a very complex, fragrant bouquet. While lighter and more reddish in color, the wines are precise, pristine and more restrained, with fresh red fruit character and floral and earthy notes, fresh but balanced acidity and structured, powerful but integrated tannins, with a tremendous aging potential.

When it comes down to German Pinot Noir, the wines from Paul Fürst (left picture) have a big role to play. He brought the villages Bürgstadt and Klingenberg onto the wine lists of the world. ). Bernhard Huber (right picture) is one of THE Pinot Noir pioneers. His vineyards in Breisgau are planted predominantly with French clones.

4: Southern Pfalz: The Villages of Birkweiler, Siebeldingen, and Schweigen

Here you find a plethora of great growers producing fabulous Pinot Noir grown on chalky soils. Warm microclimates, protected from winds by the Palatinate forest, are the secret behind vineyards like Kastanienbusch in Birkweiler, where Pinot Noir grows on the chalky parts. The same is true for Im Sonnenschein in Siebeldingen. The wines show a mineral impression with a more austere and firm tannin structure. The best wineries are the VDP members Ökonomierat Rebholz, Dr. Wehrheim, and the newcomer Gies-Düppel. Futher south, on the French border, is the village of Schweigen with its south-facing single vineyard Kammerberg, made of heavier, chalky marl soils. It produces full-bodied Pinots, with ripe dark fruits and rounded tannin structure. The best winery here is without doubt Friedrich Becker.

5: Breisgau sub-region in Baden: Malterdingen, Bombach, and Hecklingen

700 years ago, Cistercian monks brought Pinot Noir to this region, where yellowish limestone soils are prevalent. The sub-region Breisgau is a bit cooler then the sub-region Kaiserstuhl in the south, which results, together with its soil type, in pure and elegant wine styles. Bernhard Huber is the most important wine grower and he produces the perfect interpretation of this terroir. His wines are made in the best Burgundian tradition, where hidden power and elegance are key, as well as ethereal complexity, which you can only find in the best Pinot Noirs of the world.

The Kaiserstuhl (right picture), the famous sub-region in Baden, is based on an extinct volcano. Volcanic soils surface in the western parts around the villages Ihringen, Burkheim and Oberrotweil. In the northeast, around the villages Endingen or Königschaffhausen, loess is prevalent, brought by the easterly winds from the chalky alps during the ice age. The single vineyard Winklerberg in Ihringen (left picture) is supposed to be the hottest vineyard in Germany. Cacti grow on its summit.

6: Kaiserstuhl sub-region in Baden

The Kaiserstuhl is the hottest wine-growing area in Germany, and for Spätburgunder mostly German clones are planted. Pinot Noirs from volcanic soils on the Kaiserstuhl are powerful with a rustic edge, and with very ripe red fruit mingled with herbaceous notes as well as with smokiness. The structure is powerful with sinewy tannins and a mineral impression. Some of the best growers are Dr. Heger, Salwey, Freiherr von Gleichenstein, and Bercher. Wines grown on loess soils are more elegant, juicy and less smoky. Some of the best growers on these soils include R. u. C. Schneider and Knab.

7: Markgräflerland sub-region in Baden: Efringen-Kirchen

The winery Ziereisen brought the Markgräflerland on stage. His vineyard Oelberg is located in the neighborhood of a stone quarry, and soils are made of Jurassic limestone, similar to what one finds in Burgundy. The vineyard is sheltered within a dell and planted with a mix of German, Swiss and French clones. His wines pair the elegance of Burgundy with the typical fruit expression of German Spätburgunder, combined with concentration and freshness. Hanspeter Ziereisen is a rising star, and when you taste his wines it is surprising that his parents were still focused on the other agricultural pursuits this region is known for.

A stone quarry in the neighborhood shows the Jurassic limestone soil in the area around the village Efringen-Kirchen (left picture). Hanspeter Ziereisen (right picture) is the Spätburgunder star.

Conclusions

The tremendous increase in quality of German Pinot Noir has to do with several factors. Better clonal selection, knowing which clones are best suited for which single vineyard, high standards in education, a profound knowledge about viticultural and vinification techniques, climate change, and the return to the “terroir” idea (and away from sugar levels as the sole quality determinant), are driving a new classification of quality. But in the end it is the rising self-confidence of the growers that is responsible for Germany’s emergence: they no longer want to simply copy Burgundy and have started to define their own unique interpretations of German Pinot Noir. The target is to provide a distinctive contribution to the world of Pinot Noir and we are definitely on the right track.